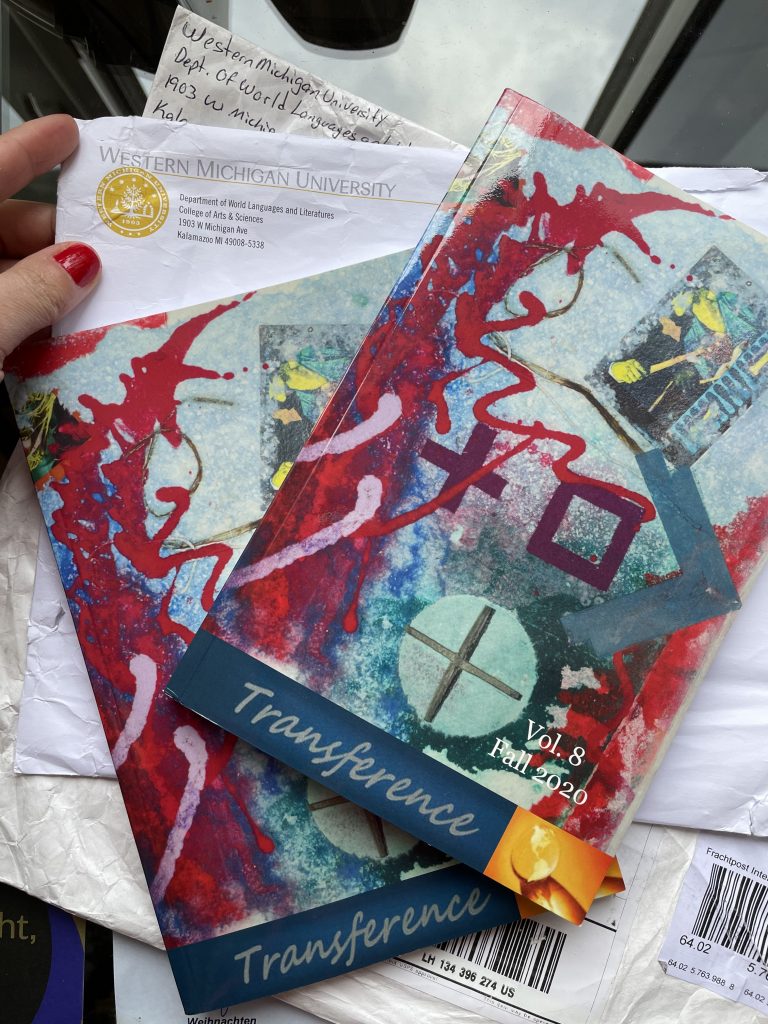

Western Michigan University / USA 2020

23.12.2020

Publikation in der amerikanischen Literaturzeitschrift: Transference

— A literary journal featuring the art and process of translation

2020

Marilya V. Reese Northern Arizona University, marilya.veteto.reese@nau.edu

Safiye Can (surname pronounced John) is an award winning poet of Circassian origins born in Offenbach, Germany whose work is appreciated for its fierce message of gender‑, species‑, environment‑, and ethnic-equality and for her fervent promo-tion of the abovementioned areas of justice as well as the sheer necessity of poetry in our lives. Not only are her poems perfor-mative—her readings before an audience are characterized by her theatrical deliverance—but her poems are also frequently visual works reminiscent of concrete poetry. Thus, it is incum-bent upon the translator to convey Can’s literal form by paying close attention to the interplay of each poem’s content and its visual representation—its actual shape. For instance, Can casts an earlier poem, not among those published here in translation, in the shape of punctuation symbol to underscore its thrust. “Integration” is written as a German, backward‑S, question mark (that resembles the symbol for a law in legalese) and is one of Can’s most famous poems. In it, Can questions the value of integration; therefore shape can be interpreted as conveying various levels of meaning: the S in its normal, frontward direc-tion, might be viewed as Can’s branding the poem with her ini-tial. Its iteration as a question mark might also be viewed as underscoring the main message of the poem, which is to ques-tion any unnuanced condonement of some majority-imposed mandate requiring that immigrants lose their cultural identity by merging with their new society.

Mirroring the shape of the German original poem is not often feasible in English, however; in “Eternal Trial” the lines are arranged in German to resemble a German lawyer’s head-wear. Since this headwear is not worn in U.S. courts, the poet and translator opted to change the form slightly to one more like a teardrop, since “plaintiff” contains the same root as the word “plaintive.”

Another level to be acknowledged and honored is Can‘s gestural metalanguage; idioms and turns of phrase too are, ideally, to be accorded equal weight. As a translator, keeping a non-German-speaking audience in mind is important when choosing idioms so that Can’s ability to be equally at home in disparate registers is evident in translation, too. The first stanza of Can’s poem “Alas” reveals a densely erudite register marked by brevity, while the fifth stanza conveys a more down to earth feel of idiom-driven soliloquy. The translator must strive to bring the same balance that was present in the original, wheth-er intellectual or colloquial. Because the full-length poem (titled “Heyhat,” an archaic Arabo-Turkic word expressing something lamentable) was six pages long, the poet and translator agreed on submission of only the two stanzas printed here as both stand-in and enticement.Equally important is a translator’s task of maintaining for the reader’s mental ear the sound of Can’s above-mentioned vocal cadences and emphases in the event that the poem ever be read aloud in English. In any case, a reader of Transferencemight be juxtaposing the sound of the original with the sound of the translated text. Length of sentence in all the above poems was borne in mind at all times and adhered to whenever possible. In addi-tion, a thrilling challenge to any translator is maintaining devic-es such alliteration and bringing in etymologically-linked words in English and German whenever it does not seem contrived to do so—an example for both these principles can be seen in the three words unser beider Band in “Alas,” rendered here as “a bond for both.” Alliteration? Check! Etymology without arti-fice? Check! Source text: Can, Safiye. Rose und Nachtigall, Wallstein Verlag, 2020, pp. 11, 19, 48, 49, 47, 46.